Just Push Play

“Those who approach life like a child playing a game, moving and pushing pieces, possess the power of kings.”

Play With Problems: Having "the power of kings" means having mastery over a situation. This power comes from having an attitude similar to that of a child playing a game. This attitude allows you to play with the issue at hand, to "move and push" its various pieces, so as to find out what works and what doesn't. As artist Jasper Johns said when asked to describe what was involved in the creative process, "It's simple, you just take something and then you do something to it, and then you do something else to it. Keep doing this and pretty soon you've got something."

This idea is reflected in a print ad, which was created in the 1960s by Charles Piccirillo to promote National Library Week. The headline consisted of the alphabet in lowercase letters like so: abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvvxyz. It was followed by this copy: "At your public library they have these arranged in ways that can make you cry, giggle, love, hate, wonder, ponder, and understand. It's astonishing to see what these twenty-six little marks can do. In Shakespeare's hands they became Hamlet. Mark Twain wound them into Huckleberry Finn. James Joyce twisted them into Ulysses. Gibbon pounded them into The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. John Milton shaped them into Paradise Lost." The ad went on to extol the virtues of reading and mention that good books are available at your library. There are several messages here, but to me the most important is that creative ideas come from manipulating your resources - no matter how few and simple they are. With this outlook, we try different approaches, first one, then another, often not getting anywhere. We use foolish and impractical ideas as stepping stones to practical new ideas. We even break the rules occasionally.

Have Fun: One of play's products is fun - a very powerful motivator. For example, Rosalind Franklin, the scientist whose crystallography research was instrumental in the discovery of the structure of DNA, was asked why she pursued her studies. She replied, "Because our work is so much fun!" Similarly, Murray Gell-Mann, the physicist who coined the term for the subatomic "quark" after a line in James Joyce's Finnegans Wake, was asked to comment on the names of the various types of quarks - "flavor," "color," "charm," "strange," etc. He said, "The terms are just for fun. There's no particular reason to use pompous names. One might as well be playful."

Finally, the renowned chair designer Bill Stumpf was asked what criteria he uses to select new furniture projects. He responded, "There are three things I look for in my work: I hope to learn something, I want to make some money, and I'd like to have some fun. If the project doesn't have the promise of satisfying at least two of these, I don't sign on."

Change Contexts: Life is filled with ambiguity, and it is context that determines meaning. Indeed, much of creativity is the ability to take something out of one context and put it in other contexts so that it takes on new meanings. The first person to look at an oyster and think "food" had this ability. So did the first person to look at a ship's sail and think "windmill." And so did the first person to look at sheep intestines and think "guitar strings," and the first person to look at a perfume vaporizer and think "gasoline carburetor," and the first person to look at bacterial mold and think "antibiotics," and the first person to look at a trapeze safety net and think "trampoline."

Reframe the Situation: Reality rarely presents itself to us with clearly defined boundaries. Rather, we impose our own order on the world through the concepts and categories of our language. If we change the words we use to describe a situation, we reframe it and change the way we think about it. For example, is the beach the end of the ocean or the beginning of land? Is the cocoon the end of the caterpillar or the beginning of the butterfly? Is water the end of ice or the beginning of vapor? You could answer "Yes" to any of these questions. This shows that a thing, idea, or issue can be understood in a variety of different ways depending on how it is framed.

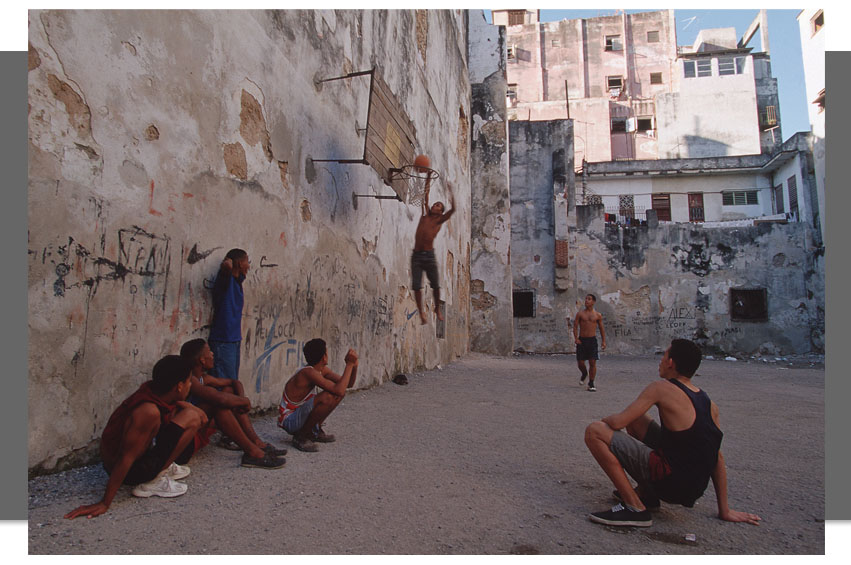

Turn Logic on Its Head: To open up your thinking, try looking at what you're doing from an "illogical" perspective. Suppose you're a teacher and ask, "What if I were less effective?" Perhaps the student would have to take more responsibility for her learning, which could lead to the development of a self-guided go-at-your-own-pace program. Suppose you're a basketball coach and ask, "How can I get my team out of sync?" The answer would be a list of unsettling things that the team could practice because they might have to deal with them in a game. Suppose you're a professional chef and ask, "What if I used less tasty food ingredients in my meals?" This could lead to ideas on how to improve the non-eating portions of the dining experience, such as the food's presentation, the service, or the decor. Doing the opposite of what's expected can also be an effective strategy in competitive situations such as sports, business, war, and romance. In most endeavors, we build up certain expectations about what the other side will or won't do. In football, for example, a third-and-long situation will typically cause the defense to prepare for a pass. In retail, you can bet that many stores will do a lot of "Back-to-School" advertising in late August. In politics, most candidates will mount a last-minute media blitz. Sometimes doing the reverse of what people are expecting (a quarterback draw play, a "Back-to-School" sale at school year's end, media saturation six months before the election) can help you achieve your objective.

Expect the Unexpected or You Won’t Find It

Roger Von Oech

Love

“If you don't love something, then don't do it. “ -Ray Bradbury

The Flow of Creativity.

Creative persons differ from one another in a variety of ways, but in one respect they are unanimous: They all love what they do. It is not the hope of achieving fame or making money that drives them; rather, it is the opportunity to do the work that they enjoy doing. Jacob Kabinow explains: "You invent for the hell of it. I don't start with the idea, 'What will make money?' This is a rough world; money's important. But if I have to trade between what's fun for me and what's money-making, I'll take what's fun." The novelist Naguib Mahfouz concurs in more genteel tones: "I love my work more than I love what it produces. I am dedicated to the work regardless of its consequences."

Another force motivates us, and it is more primitive and more powerful than the urge to create: the force of entropy. This too is a survival mechanism built into our genes by evolution. It gives us pleasure when we are comfortable, when we relax, when we can get away with feeling good without expending energy. If we didn't have this built-in regulator, we could easily kill ourselves by running ragged and then not having enough reserves of strength, body fat, or nervous energy to face the unexpected. This is the reason why the urge to relax, to curl up comfortably on the sofa whenever we can get away with it, is so strong. Because this conservative urge is so powerful, for most people "free time" means a chance to wind down, to park the mind in neutral. When there are no external demands, entropy kicks in, and unless we understand what is happening, it takes over our body and our mind.

WHAT IS ENJOYMENT?

State of consciousness. The flow experience was described in almost identical terms regardless of the activity that produced it. Athletes, artists, religious mystics, scientists, and ordinary working people described their most rewarding experiences with very similar words. And the description did not vary much by culture, gender, or age; old and young, rich and poor, men and women, Americans and Japanese seem to experience enjoyment in the same way, even though they may be doing very different things to attain it. Nine main elements were mentioned over and over again to describe how it feels when an experience is enjoyable.

1. There are clear goals every step of the way. In contrast to what happens in everyday life, on the job or at home, where often there are contradictory demands and our purpose is unsure, in flow we always know what needs to be done. The musician knows what notes to play next, the rock climber knows the next moves to make.

2. There is immediate feedback to one's actions, Again, in contrast to the usual state of affairs, in a flow experience we know how well we are doing. The musician hears right away whether the note played is the one. The rock climber finds out immediately whether the move was correct because he or she is still hanging in there and hasn't fallen to the bottom of the valley.

3. There is a balance between challenges and skills. In flow, we feel that our abilities are well matched to the opportunities for action. In everyday life we sometimes feel that the challenges are too high in relation to our skills, and then we feel frustrated and anxious. Or we feel that our potential is greater than the opportunities to express it, and then we feel bored. Playing tennis or chess against a much better opponent leads to frustration; against a much weaker opponent, to boredom. In a really enjoyable game, the players are balanced on the fine line between boredom and anxiety. The same is true when work, or a conversation, or a relationship is going well.

4. Action and awareness are merged. It is typical of everyday experience that our minds are disjointed from what we do. Sitting in class, students may appear to be paying attention to the teacher, but they are actually thinking about lunch, or last night's date. The worker thinks about the weekend; the golfer's mind is preoccupied with how his swing looks to his friends. In flow, however, our concentration is focused on what we do. One-pointedness of mind is required by the close match between challenges and skills, and it is made possible by the clarity of goals and the constant availability of feedback.

5. Distractions are excluded from consciousness. Another typical element of flow is that we are aware only of what is relevant here and now. If the musician thinks of his health or tax problems when playing, he is likely to hit a wrong note.nFlow is the result of intense concentration on the present, which relieves us of the usual fears that cause depression and anxiety in everyday life.

6. There is no worry of failure. While in flow, we are too involved to be concerned with failure. Some people describe it as a feeling of total control; but actually we are not in control, it's just that the issue does not even come up. If it did, we would not be concentrating totally, because our attention would be split between what we did and the feeling of control. The reason that failure is not an issue is that in flow it is clear what has to be done, and our skills are potentially adequate to the challenges.

7. Self-consciousness disappears. In everyday life, we are always monitoring how we appear to other people; we are on the alert to defend ourselves from potential slights and anxious to make a favorable impression. Typically this awareness of self is a burden. In flow we are too involved in what we are doing to care about protecting the ego. Yet after an episode of flow is over, we generally emerge from it with a stronger self-concept; we know that we have succeeded in meeting a difficult challenge. We might even feel that we have stepped out of the boundaries of the ego and have become part, at least temporarily, of a larger entity. The musician feels at one with the harmony of the cosmos, the athlete moves at one with the team, the reader of a novel lives for a few hours in a different reality. Paradoxically, the self expands through acts of self-forgetfulness.

8. The sense of time becomes distorted. Generally in flow we forget time, and hours may pass by in what seem like a few minutes. Or the opposite happens: A figure skater may report that a quick turn that in real time takes only a second seems to stretch out for ten times as long. In other words, clock time no longer marks equal lengths of experienced time; our sense of how much time passes depends on what we are doing.

9. The activity becomes autotelic. Whenever most of these conditions are present, we begin to enjoy whatever it is that produces such an experience. I may be scared of using a computer and learn to do it only because my job depends on it. But as my skills increase, and I recognize what the computer allows me to do, I may begin to enjoy using the computer for its own sake as well. At this point the activity becomes autotelic, which is Greek for something that is an end in itself. Some activities such as art, music, and sports are usually autotelic: There is no reason for doing them except to feel the experience they provide. Most things in life are exotelic: We do them not because we enjoy them but in order to get at some later goal. And some activities are both: The violinist gets paid for playing, and the surgeon gets status and good money for operating, as well as getting enjoyment from doing what they do. In many ways, the secret to a happy life is to learn to get flow from as many of the things we have to do as possible. If work and family life become autotelic, then there is nothing wasted in life, and everything we do is worth doing for its own sake.

Creativity Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi